The databases

There are two main databases in the nedj-nedj series: a catalogue of signs, and the examples. The second looks up the first, and saves endlessly repeating the same glyphs.

Hiero JS names

The reference database, the list of signs, does not pretend to be a list of all hieroglyphs. It contains only those that appear or are needed in the companion ‘examples’ database.

Currently there are over 1400 glyphs in the reference database, and the number grows as more are encountered that appear to be needed.

It contains:

Standard information

Gardiner number

Gardiner category

official transliteration

the actual glyph, pictorially

Information special to this database

name of glyph

respelling of the official transliteration

hiero type

category

category additional info

comments

Here is a single-line view of a small portion the database: 9 lines out of over 1400:

The central column, headed ‘JSesh’, shows the glyphs copied from the JSesh application available freely on the internet. The images could have been taken from anywhere providing elegant artwork. The database is not linked to the JSesh application in any way.

To the right is the column showing the glyph names. Why create names, when there is an official number, shown in the gold column on the far left? Because who can remember hundreds of numbers? But if a glyph looks like, say, a club, why not call it ‘club’, if that is what springs to mind; for ‘U36’ is hardly likely to. The need to identify the glyphs occurs in the companion database of examples, as will be shown.

The next column, bright blue, called ‘hiero type’, is a very rough categorisation of the glyphs into ‘tall’, ‘wide’, ‘diagonal’, ‘line’, thin’ and a few other classes.

The next two columns in tones of green are further categories into which the glyphs can be classed, somewhat akin to Gardiner’s categories.

In the yellow column in the centre left are the official transliterations of the glyphs, and in the fawn column to its right are the respellings. So official ‘dr’ becomes respelt ‘djer’, for example.

Are the glyphs in the central pink column too small? Yes, but you can review them quickly when you are familiar with most of them. But they can be looked at separately, with the touch of a button:

Are the glyphs in the central pink column too small? Yes, but you can review them quickly when you are familiar with most of them. But they can be looked at separately, with the touch of a button:

This is a page view of the fourth item in the list above. To return to the first view, hit the yellow 'SLIMMER' button.

Most of these columns were devised to help identify particular glyphs, and so enable the user to find the actual one to be identified. For what purpose? Well,imagine you wanted to read and understand an obelisk. Here is an example of the challenge, from the obelisk in Istanbul:

Detail from the Thuthmosis III obelisk in the Hippodrome in Istanbul

What do the glyphs here mean? How to begin working it out?

Perhaps great scholars of hieroglyphs just know this sort of thing, but how does an ordinary person have a go? Well, the nedj-nedj databases offer help.

First you have to know the names of the glyphs you are looking at, and some are easy. Let us identify the ones we see here, and then see what we can make of them.

We know this collection is to be read from the right, as the snake (an animate object with a face) is looking to the right, and things with faces always look to the start of the text. So numbering from top to bottom and right to left we have:

- basin

- eye

- bun

- DON’T KNOW

- pool

- cross-X

- arrowhead

- viper

- mouth

- horns

- bun

- stroke

Some of these names are more obvious (eye, horns) than others, some take a little learning but a great deal less than memorising official Gardiner numbers. And the DON’T KNOW is a challenge, for which the columns in HIERO JS NAMES might be helpful. And in fact using various clues in the columns, we identified this glyph as ‘sagbag’: like a brown-paper bag in a state of collapse in the drawing, if not so clearly thus as chiselled on the obelisk.

The first two glyphs (basin eye) probably mean ‘lord (of) work. Let us ignore them for the present.

Typing the next six glyph names into the pink bar of the examples database produces the following result:

Up pop the pictures immediately, in sequence. These pictures can be matched with those on the actual obelisk illustrated above. Under each glyph picture appears its official number, and below that in the yellow panel can be seen the official transliteration for each: sometimes with choices.

Of those appearing here, one soon learns that 3 = /a/, and š is commonly read in English as ‘sh’. So the first three glyphs suggest the word ‘tash'. The next two glyphs (cross-X, arrowhead) can be ignored, being determinatives, intended to give other scribes an idea of what the word is about — but not how it is to be read aloud. The final ‘viper’, having the sound (e)f, is a bound pronoun meaning ‘his’, or ‘its’. The word is then tash, or more fully including the pronoun, tashef.

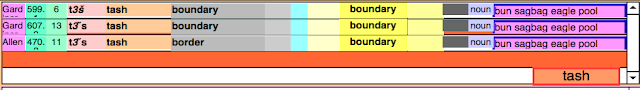

On typing ‘tash’ into a search box in the examples database, up pops the following:

You can see 'tash' in the fawn column, and its meaning in the grey column, with a standardised meaning given in the yellow column.

You can see 'tash' in the fawn column, and its meaning in the grey column, with a standardised meaning given in the yellow column.

The three ‘tash’ words therefore meaning ‘boundary’ or its equivalent ‘border’. The first of these is shown (in the source columns on the left in each of the lines) as coming from Sir Alan Gardiner’s great Egyptian Grammar, page 599 column 1, item 6. And here it is, in the database, pretty similar to the obelisk, and its analysis above:

Scribes did not always ‘spell’ in exactly the same way, but the components still make up ‘tash’, ignoring the two determinatives at the end.